Micromosaics: A World In Miniature

Elizabeth Locke

A few years ago, I had the pleasure of profiling jewelry designer Elizabeth Locke for the pages of Virginia Living. Those who know Locke’s jewelry will agree there is something very special about her work, a timeless quality reflected in the hammered gold and a sense of history reimagined in every piece. Many of the central elements in her rings, brooches, bracelets and pendants are collected by Locke herself. Every year, the designer spends a few months on what she calls a “continual treasure hunt” looking for unusual rarities and unconventional pieces that have lost their way in time. Some of these include 17th-century molds of Venetian glass intaglios and 19th-century micromosaics, the latter of which Locke collects personally. Since learning of her micromosaic collection, I’ve become enamored by the lost art form. Read on to learn more about these timeless treasures – and prepare to be inspired.

Elizabeth Locke

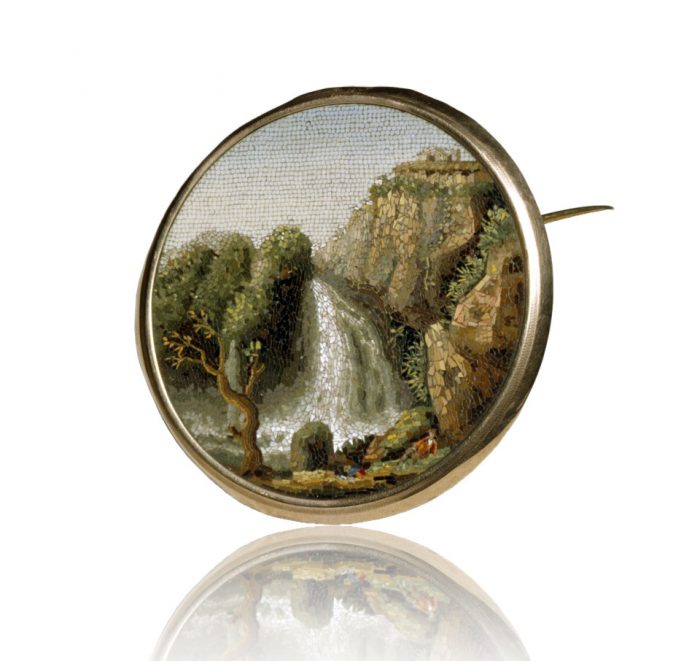

The art of mosaics dates back to Ancient Rome though the idea of micromosaic jewelry came about much later, around the time of the Renaissance. It wasn’t until the Victorian age that the art form surged in popularity. As the name suggests, micromosaics are composed of thousands of tiny glass/enamel fragments called tesserae. Some of the most valuable have thousands of pieces of glass packed into one square inch, giving them the depth, light, and illusion of a painting. Often, the raw fragments are so small that craftsmen need a microscope to work.

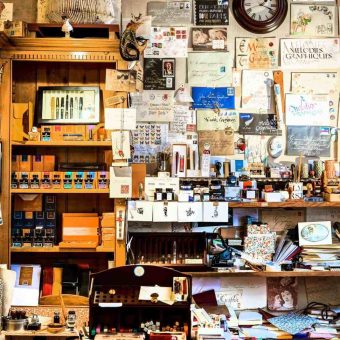

Ruby Lane

The beauty of micromosaics is that no two are the same – each is painstakingly made by hand. I’ve heard that the Gilbert Collection in the Victoria & Albert Museum has a wonderful display should you find yourself in London as does the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia.

The GIA

Many of the micromosaics you see today feature pastoral scenes or important landmarks, such as the Coliseum, for example. During the era of the “Grand Tour,” when many wealthy European and American families ventured to Italy and France, they often purchased a memento to take home with them. The micromosaic was a fitting keepsake and reminder of the places they’d traveled to.

A collection of porcelain buttons and 19th-century micromosaics inlaid in Locke’s signature 19k gold.

As with any fine art, there are many variations of the micromosaic today. The Florentines used a technique called pietra-dura — or “hard stone” — with gemstones incorporated to depict natural subjects, like birds, flowers and fruits. Animals and mythological figures were other common subjects.

Elizabeth Locke

Centuries ago, the micromosaic was also used by the Vatican to replicate religious artworks that had been damaged or faded with time. Be it these large scale masterpieces or the tiny treasures that Locke combs the globe for, I find myself endlessly inspired by these uncommon objects. Together, using tiny fragments of shredded tesserae, they give us a detailed look and a new perspective at the world in miniature.

Should you be interested in purchasing a micromosaic of your own, reach out to Elizabeth Locke or try sources such as Ruby Lane.